What on earth are anthropologists doing playing with mobile phones? The answer may be a little more obvious than you think

Anthropology is an age-old, at times complex discipline, and like many others it suffers from its fair share of in-fighting and disagreement. It’s also a discipline shrouded in a certain mystery. Few people seem to know what anthropology really is, or what anthropologists really do, and a general unwillingness to ask simply fuels the mystery further. Few people ever question, for example, what a discipline better (but often incorrectly) ‘known’ for poking around with dinosaur bones is doing playing with mobile phones and other electronic gadgets.

In today’s high tech world, anthropologists are as visible as engineers and software developers. In some projects, they’re all that’s visible. The public face of anthropology likely sits somewhere close to an Indiana Jones-type character, a dashing figure in khaki dress poking around with ancient relics while they try to unpick ancient puzzles and mysteries, or a bearded old man working with a leather-bound notepad in a dusty, dimly lit inaccessible room at the back of a museum building. If people were to be believed, anthropologists would be studying everything from human remains to dinosaur bones, old pots and pans, ants and roads. Yes, some people even think anthropologists study roads. Is there even such a discipline?

Despite the mystery, in recent years anthropology has witnessed something of a mini renaissance. As our lives become exposed to more and more technology, and companies become more and more interested in how technology affects us and how we interface with it, anthropologists have found themselves in increasing demand. When Genevieve Bell turned her back on academia and started working with Intel in the late 1990’s, she was accused of “selling out”. Today, anthropologists jump at the chance to help influence future innovation and, for many, working in industry has become the thing to do.

So, if anthropology isn’t the study of ants or roads, what is it? Generally described as the scientific study of the origin, the behaviour, and the physical, social, and cultural development of humans, anthropology is distinguished from other social sciences – such as sociology – by its emphasis on what’s called “cultural relativity“, the principle that an individuals’ beliefs and activities should be interpreted in terms of their own culture, not that of the anthropologist. Anthropology also offers an in-depth examination of context – the social and physical conditions under which different people live – and a focus on cross-cultural comparison. To you and me, that’s comparing one culture to another. In short, where a sociologist might put together a questionnaire to try and understand what people think of an object, an anthropologist would immerse themselves in the subject and try to understand it from ‘within’.

Anthropology has a number of sub-fields and, yes, one of those does involve poking round with old bones and relics. But for me, development anthropology has always been the most interesting sub-field because of the role it plays in the third world development arena. As a discipline it was borne out of severe criticism of the general development effort, with anthropologists regularly pointing out the failure of many agencies to analyse the consequences of their projects on a wider, human scale. Sadly, not a huge amount has changed since the 1970’s, making development anthropology as relevant today as it has ever been. Many academics – and practitioners, come to that – argue that anthropology should be a key component of the development process. In reality, in some projects it is, and in others it isn’t.

It’s widely recognised that projects can succeed or fail on the realisation of their relative impacts on target communities, and development anthropology is seen as an increasingly important element in determining these positive and negative impacts. In the ICT sector – particularly within emerging market divisions – it is now not uncommon to find anthropologists working within the corridors of hi-tech companies. Intel, Nokia and Microsoft are three such examples. Just as large development projects can fail if agencies fail to understand their target communities, commercial products can fail if companies fail to understand the very same people. In this case, these people go by a different name – customers.

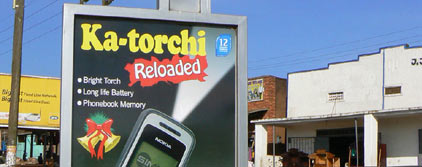

The explosive growth of mobile ownership in the developing world is largely down to a vibrant recycling market and the arrival of cheap $20 phones, but is also down in part to the efforts of forward-thinking mobile manufacturers. Anthropologists working for companies such as Nokia spend increasing amounts of time trying to understand what people living at the so-called “bottom of the pyramid” might want from a phone. Mobiles with flashlights are just one example of a product that can emerge from this brand of user-centric design. Others include mobiles with multiple phone books, which allow more than one person to share a single phone, a practice largely unheard of in many developed markets.

My first taste of anthropology came a little by accident, primarily down to Sussex University‘s policy of students having to select a second degree subject to go with their Development Studies option (this was my key interest back in 1996). Social anthropology was one choice, and one which looked slightly more interesting than geography, Spanish or French (not that there’s anything wrong with those subjects). During the course of my degree I formed many key ideas and opinions around central pieces of work on the appropriate technology movement and the practical role of anthropology, particularly in global conservation and development work.

Today, handset giants such as Nokia and Motorola believe that mobile devices will “close the digital divide in a way the PC never could”. Industry bodies such as the GSM Association run their own “Bridging the Digital Divide” initiative, and international development agencies pump hundreds of millions dollars into economic, health and educational initiatives based around mobiles and mobile technology.

In order for the mobile phone to reach its full potential we’re going to need to understand what people in developing countries need from their mobile devices, and how they can be applied in a way which positively impacts on their lives. Sounds like the perfect job for an anthropologist to me.