Each year, hundreds – if not thousands – of engaged students walk through the doors of schools, colleges and universities around the world eager to learn the art of social change. But is this the best approach? Does turning social entrepreneurship into an academic discipline give out the right message?

Classes in social innovation, social entrepreneurship and design thinking have become increasingly popular in recent years. On the one hand, this might be seen as a good thing. After all, the world needs as many smart, engaged citizens as it can get, particularly when you consider the multitude of challenges we face as a planet. But does a career in social change really begin in the classroom, or out in the real world? How much social change is planned, and how much accidental? And which approach tends to lead to the most meaningful, lasting or impactful solutions? These questions, which have occupied my mind for some time, are the ones I tackled in my recent book, “The Rise of the Reluctant Innovator”.

In our desperation to explain and control the world around us we put things in boxes, label them up and then study them to death. We look for the ‘secret sauce’ in successful ideas while trying to break down the characters and personalities of the people behind them. Finding the next Steve Jobs becomes an obsession. Books on social innovation abound, as if making the world a better place was a ten-step process which, if followed vigorously, will guarantee us meaningful change. I’m sure I’m not alone, but my experience of social innovation isn’t anything like this. Instead, I see serendipity, luck and chance play a bigger part than we dare admit. Of course that said, it’s what people do with their chance encounter that matters, not the chance discovery itself, as Scott Berkun reminds us in his best-selling book, The Myths of Innovation.

In The Rise of the Reluctant Innovator, all ten people featured took their chance. And what makes their stories even more interesting is that, in most cases, they weren’t even looking for anything to solve. The thing that ended up taking over their lives found them.

Brij interacting with viewers in Gulbai Tekra Slum, Ahmedabad. Photo: Jaydeep Bhatt. (c) PlanetRead

Brij Kothari, for example, who conceived the idea behind a subtitling tool while eating pizza, which is today helping hundreds of millions of Indian children. Joel Selanikio whose frustration at a lack of reliable health information drove him to develop a mobile data collection tool. Laura Stachel, who developed solar-powered suitcases for maternity wards after seeing mothers and babies die in the dark on Nigerian wards. Or Sharon Terry, who took on a genetic disease after a shock diagnosis that her children were sufferers.

In something of a break from conventional wisdom, in the majority (but not all) of these cases the innovators were far from qualified to take on the challenge. In a sense, they did things in reverse by encountering a problem which troubled them, and then picked up the skills they needed to rectify it as they went. This is a very different approach to the one taught in the classroom, which sees engaged young millennials taught the art of pitching, business modelling and design thinking before they’re unleashed on the world in search of a problem.

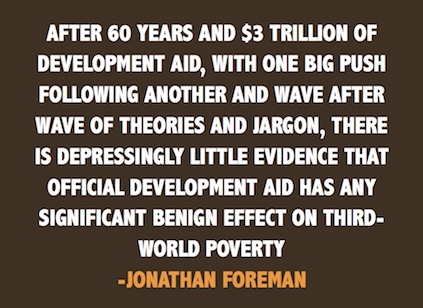

It’s also a very different approach to the one carried out by the international development community which has, over the past six decades, burnt its way through over $3 trillion in its efforts to rid the world of its social and environmental ills (causing a few of its own along the way, I’d hasten to add). The sector has effectively institutionalised development, professionalising it and making it almost inaccessible to ordinary people, including the kind of talent featured in the book.

Of course, it would be hard to justify spending any amount of money in the hope that you’d get lucky, or get that chance encounter with an innovative solution or idea. So what can we do to increase our chances of it happening?

A few tips from the book:

- Be curious and inquisitive. Ask questions. Take nothing for granted.

- Take time to understand the world. It’s complicated.

- Leave your comfort zone. Spend time with the people you’re trying to help.

- Don’t assume you can fix anything. Sit, listen, observe.

- Be patient. Remember this is a life-long journey, not a three month project.

Finally, work on something that gets you out of bed in the morning (and that will continue to do so for years to come). Make it something that switches you on, that fuels your passion. This is probably most crucial. Howard Thurman was spot on. “Don’t ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive and then go do that. Because what the world needs is people who come alive”.