I’m old enough to remember the euphoric tech-optimism of the mid-2000’s, a time when the Internet and mobile technology were blazing a trail across much of the developing (read: offline) world. Soon, the argument went, everyone would have a voice and that could only be a good thing for human rights, democracy and economic empowerment, to name a few.

And for a while it was. But not so much now.

I was incredibly fortunate to get caught up in what was fondly known back then as the ‘mobile revolution’. As long ago as 2003 – that glorious Nokia-dominated pre-smartphone era – Richard Burge and I carried out research in an attempt to capture and document how phones were being used across Sub-Saharan Africa, and what lessons could be learnt from that use. Most of the evidence was anecdotal, and it’s funny to think that one of our conclusions was that mobile phones had potential for conservation and development work, but whether or not they would reach it was unclear. I still refer to that time as a ‘golden age of discovery‘, one where you could fit everyone innovating around the technology into a small room, and where you could try almost anything in the knowledge that it had likely not been tried before.

Of course, those days are long gone. And so has all that optimism.

We all know you can’t blame the technology for how people choose to use it. Mobile phones and the Internet have clearly revolutionised communication and access to information, but their widespread use has also contributed to the erosion of democracy and societal cohesion, particularly over the last 15 years. The rapid spread of misinformation, polarisation through algorithm-driven echo chambers and manipulation of public opinion via social media have weakened trust in democratic institutions and fragmented communities. The evidence is all around us.

Dumb phones, once occasional tools of convenience, have become smart and are now constant companions, contributing to rising levels of anxiety, attention disorders and feelings of isolation, especially among young people. Today’s always-on culture, social comparison and digital overload have created a mental health crisis as we struggle to disconnect from a world designed to keep people scrolling rather than reflecting, connecting or engaging meaningfully in civic life.

Steve Jobs launching the original iPhone in 2007

But we are where we are. And it could have been so different. Jonny Ive, designer of the iPhone, has publicly acknowledged the down side of one of his greatest triumphs. ‘Humanity deserves better‘, he says. And it does.

My contribution to the ‘mobile revolution’ was the founding of kiwanja.net and the creation of FrontlineSMS. I always did my best to take something of a back seat, to remain relentlessly focused on the end user and to provide tools and access to information and resources that helped social and environmental activists do their own work better. It’s with fondness that I remember a conversation I had with the marketing team at National Geographic when I won my Explorer Award in 2010. I was asked for photos of me in the field working with FrontlineSMS users, and I didn’t have any. Users took the software and did all the work themselves, I told them, without needing me to get in the way. I remain convinced that this is why it worked so well, and the reason it created genuine empowerment and excitement.

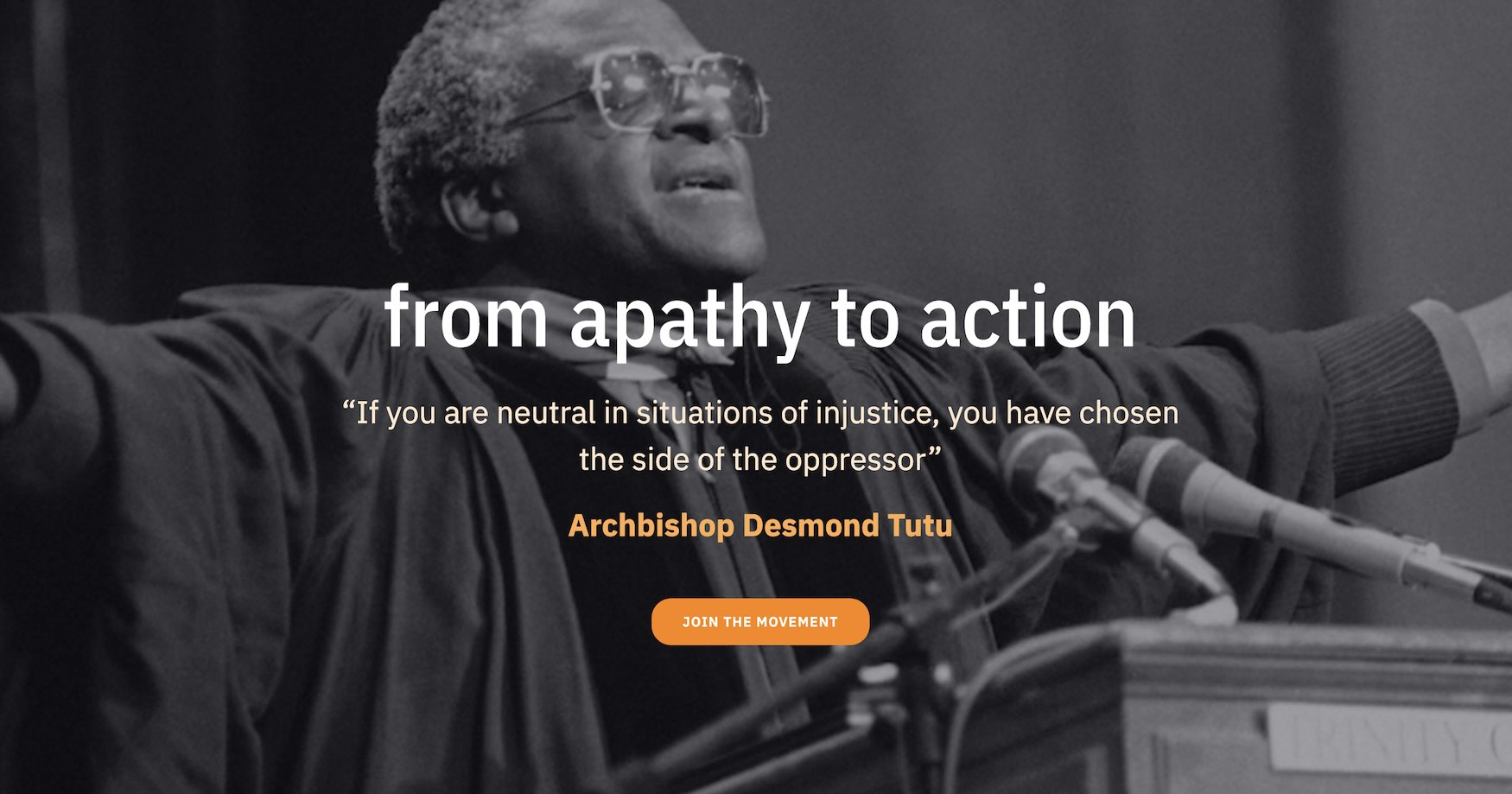

That approach seems less compelling today and, as I look back exactly 20 years on, it feels like time to figuratively ‘come in from the cold’. Remaining quiet or passive (or whatever you want to call it) doesn’t really cut it anymore as so much crumbles around me. The big question, of course, is what to do. What might make a difference? How might I contribute? Is it even worth trying? I could easily write a book about all the things that trouble, anger or upset me, but there are probably five that spring immediately to mind.

The erosion of US democracy

Increasing political polarisation, attacks on voting rights, disinformation and the undermining of democratic norms have placed the US under serious internal strain, with global implications for us all.

The ongoing crisis in Palestine

Decades of occupation, repeated military conflict and a deepening humanitarian catastrophe have left millions of Palestinians without security, rights or hope, raising urgent questions about justice, statehood and international accountability.

Buildings hit by Israeli airstrikes, Gaza (Photo: Hatem Moussa)

The climate emergency

Extreme weather, rising sea levels, biodiversity loss and worsening climate-driven inequality threaten global stability. Despite overwhelming scientific consensus, political inaction continues to delay any kind of meaningful progress.

The global migration and refugee crisis

War, climate change, economic collapse and persecution are displacing millions worldwide. Yet the response from wealthier nations is often defined by border walls, detention centres and xenophobic policies rather than compassion or responsibility.

The rise of authoritarianism and digital surveillance

From China to Hungary to parts of Africa and Asia, autocratic regimes are consolidating power, often using digital tools to monitor, censor and suppress dissent. This trend threatens human rights, freedom of expression and global democratic norms.

I’ve been fortunate to have built more than enough social capital over the years, and much of it continues to fuel the work I do today. But despite a life largely spent trying to doing good, it no longer feels like enough. Boots on the ground might be a more appropriate response, causing ‘good trouble’ as US Senator John Lewis described it. “Speak up, speak out, get in the way. Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America” was his civil rights rallying cry.

What it boils down to, at the end of the day, is what we have to lose by taking action, and whether we’re prepared to do it. Throughout history many people have paid the ultimate price for standing up for what they believe in, for getting their boots on the ground. What could I possibly lose for standing up and speaking out compared to those who have given their lives?

Plenty of things keep me awake at night, in particular a sense that I’m not doing enough. Having young children who will inherit this mess doesn’t help. But not knowing what to do is only a part of it. We can always start by speaking up.

So that’s where I’ve decided to start. beginning with this post today. Who will join me?