A few weeks ago I took part in a weekend retreat at the Cambridge Buddhist Centre, something I’ve wanted to do for a long time. Meditation, Buddhist teachings and vegan food were the order of day, but for me the greatest insight came from conversations I had with the monks about their journeys, beliefs and opinions on Buddhism and modern life. Seeking personal enlightenment felt all well and good, I said, but how does that square with issues on the ‘outside’? You know, such as my frustration and anger with all the needless conflict and suffering going on around the world?

Despite many great conversations, I never did get any answers that sat well with me. As someone whose work has been driven by empathy and rooted in action for so many years, stepping back and focusing my energies on how I deal with my own feelings didn’t feel like much use to anyone experiencing the suffering.

I’ve had plenty of time to think about this, and thought it might be helpful to write some of it down. But first, a caveat. While it may not have given me the answers I sought, Buddhist thinking does offer plenty of tools for engaging with situations beyond our control without falling into despair, reactivity or hatred. While Buddhism does not offer geopolitical solutions to problems, it does provide a framework for how individuals and communities might respond to suffering with clarity, compassion and courage. I’ll share some of those tools here, starting with non-attachment.

The Principle of Non-Attachment

Buddhism teaches us that our own suffering often arises from our attachment to outcomes. When we’re overly committed to a desire for peace, or for justice to be delivered in a particular way, we’re more likely to experience intense frustration or helplessness when nothing ever seems to get any better.

We’re also told that this non-attachment doesn’t mean apathy or indifference. Instead, it’s meant to allow people like me (and others far removed from the conflict) to engage constructively without being overwhelmed by feelings of rage, grief or despair. This is supposed to help us remain steady in the face of intractable suffering, continuing to care and act where we can.

To be honest, I find the application of this principle pretty difficult, particularly in the face of intolerable human suffering. Maintaining emotional distance doesn’t sit comfortably with me.

Compassion and the Recognition of Shared Suffering

Buddha taught us that all humans suffer and seek freedom from that suffering, and that compassion comes about naturally when we acknowledge this shared vulnerability. The trouble is not everyone does. With the Palestinian conflict, for example, a Buddhist approach would encourage all sides to see the humanity in everyone – Israeli and Palestinian – recognising that fear, trauma and loss are not one-sided. Buddhism invites us to hold both communities in our hearts without taking sides in a way that leads to any kind of dehumanisation.

This is another tricky one, especially in the face of what feels like relentless injustice and violence, but it’s critical for building true peace (think: Archbishop Tutu and South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission). I hate to say it, but this is another concept I have to work particularly hard at. Luckily I’m a good listener, and that might be a helpful starting point.

Right Speech and Deep Listening

Buddhism encourages speech that is truthful, kind and unifying. Sadly I don’t see much of this, particularly from our political leaders (don’t even get me started on social media). Buddhism also teaches the value of deep listening, and asks that we truly hear the suffering of others. Polarised narratives often dominate public conversation about conflict. A Buddhist-informed approach would encourage listening deeply to all sides and all stories without defensiveness or premature judgment. The objective here is to foster empathy and reduce the tendency to vilify or dehumanise the ‘other’.

The Impermanence of All Things

A central tenant of Buddhism is that nothing is fixed, and even the most entrenched suffering and conflict will eventually change (and hopefully improve and go away). Recognising this allows us to maintain hope and counteract despair by reminding us that today’s reality is not forever, and that seeds of peace, however small, can take root at any time. While any of this is hard to disagree with, I struggle with relying on others to plant those seeds. I’ve always felt that I needed to be there doing the planting with them. Maybe not.

Acting Without Ego

Buddhism discourages acting from a place of self-righteousness or moral superiority. This is perhaps one of the easiest concepts for me to grasp. I’ve worked hard throughout my career to suppress ego, and to genuinely listen to and empower others without agenda. In activism and humanitarian response, acting without ego encourages humility. We can all support peace, justice and dignity for all without needing to be right all the time (whatever that might look like) or to dominate the discussion. All of this reminds me of the importance of putting the needs of those suffering front, right and centre – not any opinions we might have about the conflict.

Mindfulness and Inner Peace

Mindfulness allows us to observe our emotions without being consumed by them, something I’m slowly getting better at. In moments of helplessness, mindfulness allows us to notice our pain without turning it into hatred or numbness. This creates space for grounded, thoughtful action rather than reactive outrage. Sadly, in today’s short-term attention economy, sitting back and reflecting before reacting and responding is becoming increasingly rare. I sleep on things a lot more these days before deciding what steps I might take, if any.

FINAL REFLECTIONS

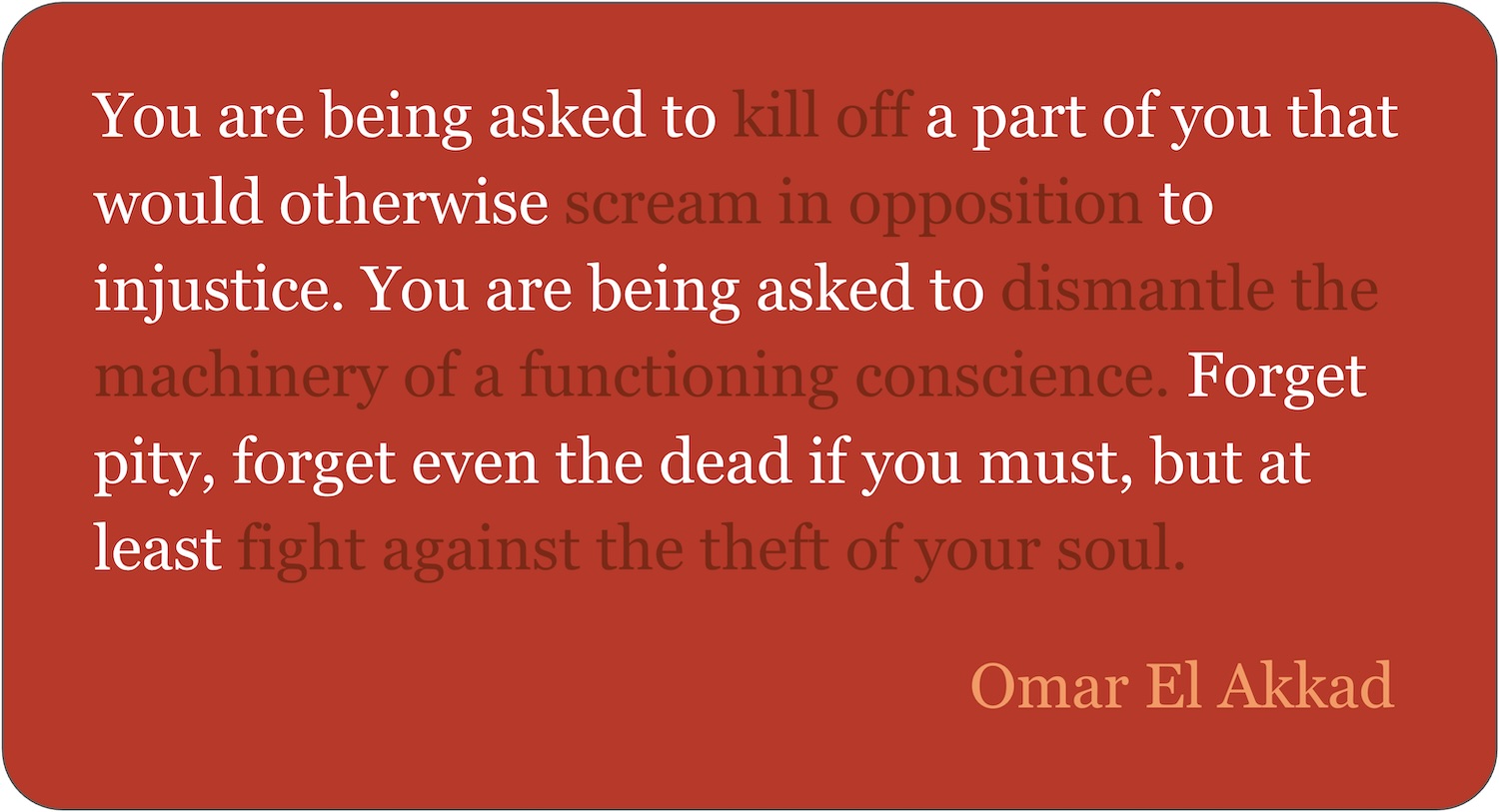

In all my Buddhist reading, study and practice over the last couple of years, trying to balance my deep feelings about conflict and human suffering with my gut reaction to get active and do something about it has been by far my biggest challenge. I get the need for enlightenment, to better understand ourselves and to manage how we process things, but I’m yet see how any of that makes much of a difference to people being bombed out of existence every day.

In its defence, nowhere does Buddhist thinking ask us to withdraw from injustice, but it asks us to engage in a way that does not create more suffering. It encourages action rooted in understanding, presence and compassion, all qualities that are desperately needed in the face of seemingly impossible and never-ending conflict. Thich Nhat Hanh, a Buddhist monk who lived through the Vietnam war, often said that ‘Peace in the world begins with peace in ourselves.’

He’s probably right. I’ll let you know if I ever get there.